Interview Archives

CorpsStories Exclusive Interviews

with Extraordinary Marines and Supporters

On All Sides

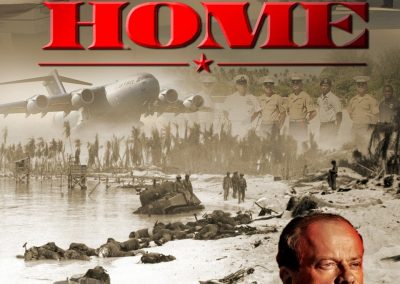

“Until They Are Home” Capitol Hill Showing

10 November 2012

Editor’s Note: This is our third feature about the films of Steven Barber. I took the liberty to approach this piece in an altogether different manner. I hope it doesn’t offend. P.S. A ‘suit’ as referred to below is a Marine or former Marine providing security, officially or unofficially. MB

The story is not in the story. The story is in the Marines and leaders of Marines and supporters of Marines who have told and been moved by the story. The graves are gone. And even if they weren’t gone now, they’d be gone soon.

“The ironic thing is that these graves are on an atoll.The island is sinking. They would be gone in 50 years anyway.” This from Leon Cooper. Cooper wrote the story. And on September 19, 2012, his story Steven Barber with footage by Tarawa Marine survivor, Norm Hatch.

Suit’s thumbs met at the top of the steering wheel of that new black sedan as he stealthily traversed D.C. highways, tight traffic and narrow one-ways. While I researched, made notes, fielded players wirelessly.

A Capitol Hill Police officer gave nod to a sweet spot just a few car lengths away from our entrance. After looking us over. A long gaze at himself, that cop knew only a few degrees of separation existed between them.

Past security into a granite, marble, bronze, vast and breathtaking hallowed halls of the most stable government in world history’s seat. Being directly descended from her first president’s grandfather, and her most important explorer’s mother, ancient connections relayed familiar whispers in my ear.

The souls of these servants are on all sides. This movie was borne from such unrested warriors and we living have heard their calls thanks to a few. Cooper, Barber and Hatch have sacrificed their lives and livelihoods to respond to their understood rage.

Not five. Five would be a news story worthy of international publication. Not fifty. Fifty would receive an act of Congress to resolve post haste.

Five hundred. Five hundred missing graves of the 1,500 Marines killed like the fish in a barrel they were as they descended upon Tarawa’s beaches in November 1943.

Crossing lobbies and down broad staircases found Barber straddling a lone chair, head buried in his arms across the top of the chair’s back. A young woman stood behind, digging her hands deep into his neck.

“What in the world, Steven?” my voice echoed across thehundreds of feet between us.

“Oh, hey Meriwether,” his blue eyes shining upon a now lifted head. Lesson learned: never expect Barber to be the aloof Hollywood type. Always accessible and sometimes vulnerable, he may be California pretty but his mission has yet to wane from center.

Suit made short work of the crossing, reaching back a hand to help my high-heeled legs keep pace. Neck pain familiar territory, he asked Barber if he was ok.

“Sure,” not convincingly Barber held his upper half in an odd position as he introduced his sister now masseuse. “Go on in, it’s already started,” Barber said as evil thoughts of traffic’s effect on my suit’s promptness edict flashed across his face.

Not only were these heroes of war Cooper and Hatch present, they’re heroes of a lifetime efforts.

Soon inside, we’d find important players attending;including Virginia Congressman Jim Moran (serving his 11th term)who’s absolutely a master at walking the tightrope between Washington politics and supporting our military not only today but it’s history as well.

House Member from Illinois, Chicago specifically, came Dan Lipinski and his wife. Lipinski is to be thanked for the event occurring at all. He has come to have an appreciation, respect and honor for Barber’s documentaries, not only “Until They Are Home”, but also to its prequel, “Return to Tarawa”. (Please click links for our recent pieces on these two films.)

Finding spots in a high back row, footage of then Staff Sergeant Norm Hatch’s “With the Marines at Tarawa” rolled. My suit sat at attention as did uniformed Marines all around us.

I shook off being drawn into the film, having seen it’s east coast premiere months earlier. I now had other priorities; get art,observe and note others. Quietly I reached for pen and pad, realizing the best pictures for my story would come from spots other than here.

Unthinkable on any assignment before, but with complete trust now, I handed my camera to the suit. Eye contact before he silently slipped away. Soon he was invisible to anyone but me. Sliding low and silently between rows he made adjustments to shutter and aperture killing any thought of an attention-drawing flash.

Stills of the audience would be followed by stunning and rare captured emotion of the atrocity’s only two witnesses, Hatch and Cooper. A tiny nod his way across a hundred dark yards of theater was heard.He redirected, catching a standing Sergeant Major’s questioning face.

for once was working out just fine.

Sharing an assignment (Photo:James Lafferty, Leon Cooper, Steven Barber) He’s a Navy officer with no interest in the press. “Who are you with? What outfit?” Cooper took my questions last, as we mulled around upon the movie’s conclusion.

I replied that I’m an independent journalist. First his eye brows raised, then knit. “Yeah? Well, what do you want? What kind of journalist?” he said sarcastically.

No time to explain that I smoked on the breezeway at Montgomery Blair High School with Matty Drudge or what independent online aggregates are, so I took the slug on the chin and moved on. “I’m on your side.”

“Humph.”

Change tactics quickly; let the suit come to my rescue.I needed a distraction to bring Cooper back around, and off the defensive – although I’m still unclear how I got his back up. “Sergeant Lafferty lived along time in the Pacific after his Marine Corps days, Papua New Guinea.” I said turning toward his stately self.

With my three-inch heels I easily towered another six over Cooper. How was he able to look down at me, then? He did, and I had to consciously remind myself that I was not Third Class Journalist Meriwether Ball and he was not my dissatisfied unit commander.

I had to remind myself that he IS a furious leader of Marines killed swarming shores he directed them toward – Marines whose graves that HE discovered are likely lost forever.

And now he was looking down on my suit’s six-foot-somethingness, sizing him up. “Really? Where in New Guinea? And why the hell were you there anyway?” Ok, maybe not such a good tactic after all.

Ninety-three years young, no more than five-foot-nothing, and leaning on a cane. That cane was a weapon at the ready and anyone’s a fool not to know it.

Admitting defeat I lodged a few more unhappily answered questions then cut him loose. Who was I to demand anything of him? No one.

These 500 lost Marines had my suit’s undivided attentio n– and heartbroken concentration. I knew the Marine noncommissioned officer lived inside Lafferty, I’d just not seen him up close before.

Four hours earlier former Marine, and on this day my trusted confidant and most days my companion, Sergeant James Patrick Lafferty was in all out warfare with a crease on the upper left arm of the tailored white shirt under that lean, black wool suit. Sleight of hand and heated weapon won. Soon minutes would pass and pass some more as he bloused out that fabric with the precision only a descendent of First Sergeant Ellis Cozine could possess.

Cozine owned the drill field as a Hat. Later he’d take on machete and machine-gun wielding Zairian authorities attempting to search his gear upon arrival to take over a locked-down U.S. Embassy. Outnumbered and heavily out-gunned, this wild-eyed Texas child of two Marines gave no ground. He and his gear soon arrived at the Kinshasa compound untouched and uncompromised.

This was not dressing. This was representing. Himself had the passion of flawless presentation in his eyes . The Commandant was not only invited to this Capitol event – but may actually surface. And Cozine was watching. Not literally. But somewhere in the back of my suit’s mind, or heart, his part of the Zaire embassy inspection would not fail. Not18 years ago. And not today.

Shaving and shining and trimming back sixteenth-inch vagrant threads were met with silent gliding actions of excruciating attention to detail. There would be no mistaking his background. His point of reference. His priorities. His loyalties. His courage. His honor. His commitment.

Eye contact only when delivering me wordless instructions put us on the move.

As the crowd dispersed and I began to pack up, I wondered about this documentary film maker whom I’ve written about three times now.

What voice told Barber that day years ago to turn his car around, attend a Los Angeles, largely self-published book fair, and walk right up to Cooper’s table lined with his tome about Tarawa?

And what voices led him to follow the story to JPAC and to Tarawa and to hunt down credible famous faces to narrate these films?

As Barber, his producer Tim Shelton and Cooper loaded the elevator after leaving my suit and alone, silence ensued.

Soon suit wrapped an arm around me and lifted the camera to capture us there and then. “Smile, Meri.”

“Sir? Madam?” a gentle male voice called from behind us.

“May I take a picture for you?” We turned to find a handsome middle-years Asian couple and more facing us from the center of the immense foyer.

He took a shot that will last in our minds for decades.But that’s not important. It is who that man is which is important.

Larry La is known publicly as the highly respected owner of D.C.’s Meiwah restaurants. He shared his mission calling on Congress this night regarded the not-so-pleasant subject of the horrific mistreatment of innocent Chinese Americans living peacefully on our soil during the 19th century, The 1882 Project.

Then he said words which will ring in my ears the rest of my life. “My nephew was a Marine. He died in the war.”

“Who was your nephew?”

“BinhLe.”

Oh, my God.

Years had passed since reading that name. Pages of events between then and now fluttered across my mind. I froze. Not the tiny Corporal Binh Le whose story began to read aloud from a secret spot deep in my heart.

Not from where so many stories of fallen Marines who died in Iraq and Afghanistan came through my mentor John Monahan’s email to mine. For years we published their sacrifices as reported in hometown news.

But Binh Le was different. He used himself as a distraction to that truck full of explosives, diverting it from its intended 2004 destination of the Marine camp where hundreds worked and lived, Marinesblissfully unaware as it approached Le’s check point.

Not even American. He came here from Viet Nam as achild. He left his family to live with an adopted Virginia family who’d rearhim to the day he enlisted. A day he’d dreamed of from early adolescence.

Awarded posthumous citizenship, he was recommended for the Silver Star, and buried at Arlington.

And here was a member of that adopted family issuing a simple gracious gesture to strangers. Here at the showing of a movie about lost, fallen Marines.

The astonishing moment of spiritual confluence could not be denied.

These Marines who’ve died have souls which stir the living who listen, I am certain. Call this Christian woman a heathen, but sobeit. Barber and Cooper drive their lives to serve those who’ve been deprived of deserved honor. They have these Marines in their heart and their minds.

They have Marines on all sides.

END

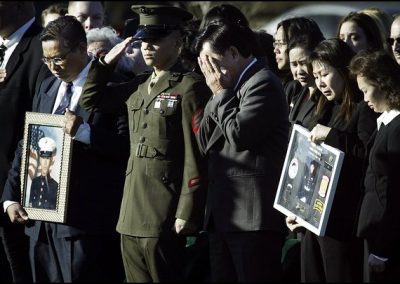

ME/LE

SLUG:ME/LE DATE:12/22/04 Neg#: 163161 Photog:Preston Keres/TWP LOCATION: Arlington Cemetery, Arlintgon, Va. CAPTION:Arlington funeral for Marine Cpl. Bihn N. Le, of Alexandria, Va. Here, (L to R) Luong La, uncle; Marine Marine Sgt. Suong Nguyen, interpreter; Lien Van Tran, natural father (hands on face); Kim Hoan Phi Nguyen, natural mother (holding awards), Puc-cuc Thi Tran, aunt. StaffPhoto imported to Merlin on Wed Dec 22 17:30:07 2004